Some tools earn a place in the shop.

A few earn your trust.

This bench earned both.

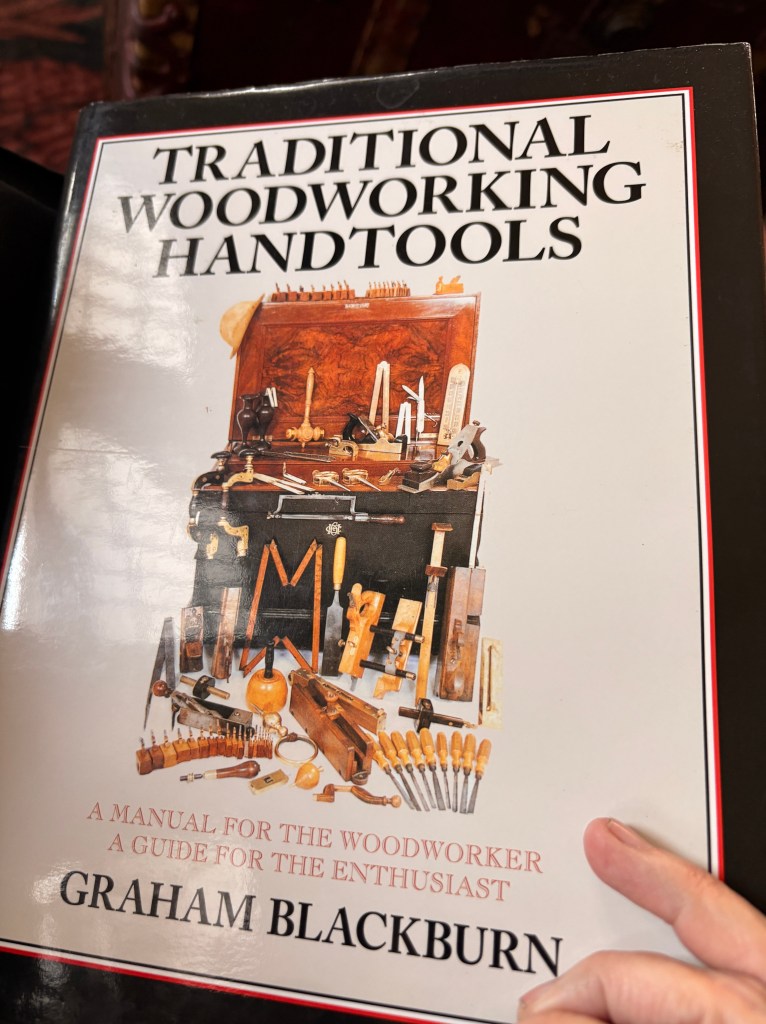

I bought this bench in the early 1990s from Graham Blackburn, the highly regarded woodworker, teacher, and writer whose work shaped how many of us came to understand traditional woodworking. Graham was a longtime contributor to Popular Woodworking and Fine Woodworking, and the former editor of Woodwork magazine. His writing was rooted in firsthand experience and a deep respect for tools that existed to be used, not admired from a distance.

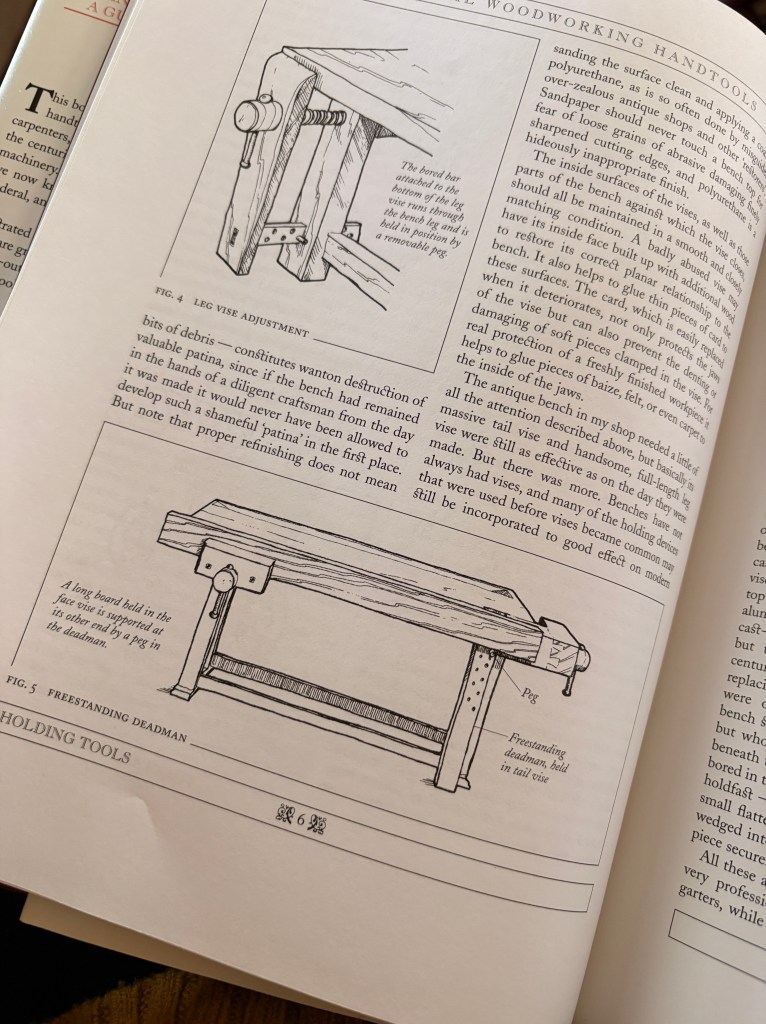

Graham later wrote about benches of this type in Traditional Woodworking Handtools, in a chapter titled “The Classic Workbench.” The chapter documents a classic workbench complete with wooden-screw vises and a sliding deadman, illustrated and explained as a working system rather than an idealized form. Whether the drawings represent this exact bench or one built to the same pattern matters less than the fact that the form, proportions, and function are clearly shared.

What we know about this bench is straightforward.

Graham found it in Connecticut, where it had likely been built and used as a cabinetmaker’s bench. Its construction and scale place it firmly in the late nineteenth or early twentieth century. It is long, heavy, and unapologetically solid, the kind of bench meant to stay put and support sustained hand-tool work.

Graham later moved the bench west to California, where we met it. We drove to Inverness, a small coastal town north of San Francisco, to pick it up. Loading a century-old workbench of this size into the back of a 1987 Toyota Land Cruiser was an exercise in commitment. The bench extended well beyond the rear gate, and the six-hour drive home was spent with Jan watching the road behind us far more than the one ahead.

Over the past thirty years, this bench has lived and worked in California, Washington, Missouri, and now Oregon. It has never been treated as furniture or display. It has remained intact and in continuous service, moving only when life required it to.

As a classic workbench, its features are purposeful and direct. The wooden-screw vises provide exceptional holding power with fine control. The sliding deadman supports long stock during planing and joinery, making it indispensable for furniture and chair work. The bench’s mass absorbs vibration and rewards deliberate, hand-driven work.

Graham observes that, “portions of the bench’s undercarriage show a series of evenly spaced bored holes characteristic of early rope beds common in 18th-century New England. These beds relied on bedcord threaded through the frame to support the mattress, leaving a distinctive pattern of borings in the structural members. Blackburn suggests that the presence of these holes indicates the bench was likely built, at least in part, from reclaimed sections of an earlier bed frame, repurposed when the original bed was no longer needed. Rather than diminishing the bench, this reuse speaks to the practical mindset of early craftsmen, who valued sound material and adapted it for continued service.”

This bench has supported decades of Windsor chairmaking, custom furniture, and the steady, unremarkable work that fills a life in the shop. Its surface bears the marks of that use honestly. It has been maintained as needed, never refined for appearance’s sake. Wear here is evidence, not damage.

In Traditional Woodworking Handtools, Blackburn argued for benches that earn their place through use. He cautioned against turning them into storage surfaces or decorative objects, and instead framed them as tools whose value is measured by how well they support the work placed upon them.

That idea has stayed with me.

This bench carries a history that began long before it entered my shop and will continue long after it leaves. For now, it stands beside me as a working partner, steady and familiar, doing exactly what it was built to do.

Leave a comment